All this has changed. From the first moment I set foot inside Omar Farroukh Public School, everything seemed different. I knew then that I was out of my comfort zone which even seemed like a flying gas bubble, gone with a blink of an eye. The assistant principal greeted me with a glimpse all the way from the administration door to the concrete edge on which I was sitting alone. She approached me, pointing to the Palestinian Hattah (Keffiyeh) hanging from my shoulders to my waist, saying, «What's this?» She meant that I was violating the school’s rules that prohibit the display of political symbols on campus. Yet at the time, I thought she didn't know the black and white patterned cloth. My naivety pushed me, to explain to her in my own vocabulary about the uses of the Hattah and its symbolism to the Palestinian people, but she ordered me to remove it and not bring it back again. I was so angry given that I was so proud to wear it on my first day because it was a gift sewn by a friend of my grandmother «Sawda».

I grabbed the left hanging end of the Hattah, folded it gently, and locked it in the school bag. My heart was beating so turbulently, and I felt something inside me break. The sound of the bell was different. I walked towards the students who lined up in the courtyard within seconds. One teacher helped me find my class and made me stand in the front. The principal greeted us welcoming the new school year, and then music rang all over the place, and the voice of all the students rose, chanting: «Kullunā lil watan, lil ‘ulā lil ‘alam, Mil’u ‘ayn iz-zaman, sayfunā wal qalam» (All for the country, for the glory and flag, our valor and our writings are the envy of the ages). I knew that this was the Lebanese national anthem, as I knew its words from the national education lesson. Although I studied at UNRWA schools for Palestinians, the curriculum was mostly Lebanese. - Yet my country is not Lebanon! So why are students staring at me for being silent while they stand up for the anthem? I was standing there, feeling as if my original nationality and my homeland culture were stolen from me in this tight space. Other teenagers were unintentionally exerting a sort of social pressure on me, so I turned around my lips moving like everyone else and singing to the Lebanese flag.

No one in class called me by my name; I was «the new student» for students as well as for teachers. That's how they recognized me and addressed me. That day, I couldn’t blend in class because I was so busy figuring out why I was being treated like this. Was it because of my different nationality and culture? Difference is not a problem. It is rather a right. This is what I learned with my sister in one of the awareness seminars we attended at one of the Non-Governmental Associations in the camp about children's rights. My right to my name, nationality and identity must be protected in accordance with Article 8 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, and the Palestinian Hattah/Keffiyeh is part of my identity. - Although I was convinced of what I have learned, but what happened to me made me angry. I went back that day to Burj El Barajneh camp furious. I thought about leaving school, but it was impossible, because I'm the one who asked to move to a new school. I threw my bag at the house entrance door violently. My grandmother, Sawda, was sitting in the center of the house facing the open gate, inspecting the red chili peppers lined up on a sheet on the floor. She raised her head slightly and called me, «Hey, mischievous girl, why did you throw your bag this way? Did something bad happen?» I gave her the Hattah back and told her I wouldn't need it anymore. She screamed at me with her usual voice because she thought it meant nothing to me. So I explained to her and told her what happened at school and how the assistant principal scolded me and made me hide the Hattah, and added «they even wanted me to become Lebanese, they didn’t put the Palestinian anthem, only the Lebanese!». Grandmother Sawda laughed at me, for my overreaction and asked me to bring her the hand pepper grinder from under the staircase. She took it from me and put a pot under the grinder strainer, then started shoving the dried pepper pieces into its nozzle. «Now I want to show you that you are the one who made a mistake today,» she said coldly while I was stunned after hearing her last sentence, and because she knew me well -the only granddaughter who received the honor of a bedtime story years ago- she added: «Be quiet until I finish».

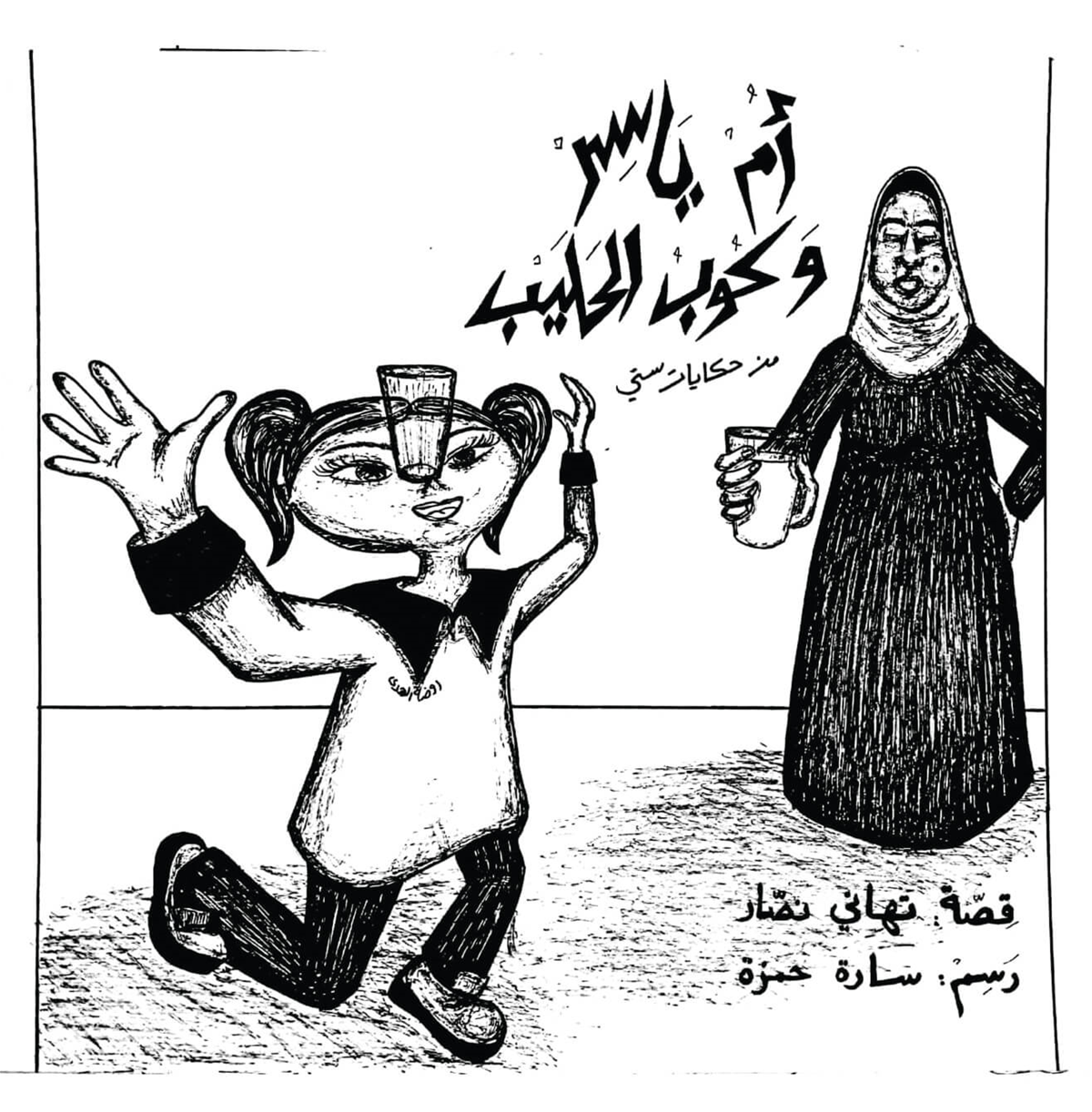

Sawda taught me that what happened was normal. Why would they play the Palestinian anthem in a Lebanese public school? Do UNRWA schools repeat the words of the Lebanese anthem every morning? Moreover, participating with them does not mean that I lost my identity or became Lebanese. According to her, «You are of a Palestinian descent inherited from your ancestors, from Kweikat, the village of your grandfather and grandmother. That’s something no one can take from you because it is in your blood. Everyone in this vast world, my dear grandchild, has a country, an identity, and traditions that resemble him, which he must preserve.» Adding that we have been living in Lebanon since the Nakba, and it is good that the two cultures get mixed because this enriches both of them, citing my grandfather's shop outside the camp, where he deals with Lebanese and customers of different nationalities. That day, my grandmother, did not forget, of course, to mention my mother's parents, who had acquired the Lebanese nationality due to political naturalization circumstances, but who still lived in the camp with their close ones. Sawda’s words made me realize that my lack of awareness is the real reason behind my anger. I was ashamed of my inappropriate behavior in front of her, but she noticed my red cheeks and concluded: «Your name is Tahani Nassar, no one calls you other than by your name. Before you go and change your clothes, remember that the Hattah is not a political symbol, tell the teacher that your grandfather used to wear it on his head while working in the land of Kweikat.»

That day I learned a lot. Sawda has always been a good teacher, despite her strict personality and sharp nature, which most family members and perhaps neighbors could not bear. I ask myself today, would I have become who I am now, if it weren't for her wisdom and the camp that shaped my national identity awareness? It was not easy for my ancestors who crossed the Palestinian-Lebanese border on foot in 1948 seeking a safe haven for their children. Perhaps the camp, and for many reasons, is not an ideal place for a child. - Yet it certainly was for me and my generation a place that provided us with our obvious rights as children, considering it was a safe place where we grew up on its soil, and between its narrow alleys and humble quarters, playing the «zahfa» and running behind a Kaak-seller's cart who forgot to give us a handful of thyme wrapped in thin paper. In the camp, the houses' doors remained open since the morning, and passers-by could see the residents gathered around a morning coffee talk or an afternoon teacup. The walls of the camp are filled with drawings and sayings that contributed to strengthening our identity, from the full map of Palestine listing the names of the displaced villages and towns of upper Galilee, to the image of Hanzala, who was our friend when we were his age and endured our wickedness the day the wax crayons melted from our extreme wall rubbing in order to change the color of his clothes. In short, it is the place that gave us our right as children to exercise our Palestinian identity in terms of language, customs and traditions, and taught us from a young age that we are of a Palestinian nationality in a Lebanese environment whose children hold the nationality of their country, because that is their right, our right, and the right of each child in the world.